Intimate Partner Violence: The Role of the Obstetrician or Gynecologist

Authors

INTRODUCTION

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is thought to be the most common cause of serious injury to women; it accounts for more than 50% of female homicides.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 National statistics show that between as many as 2 million women each year are beaten in their homes and that partner abuse occurs in 25% of American families.2, 9 In more than 50% of homes where women are battered, their children are also victims of abuse.3 Medical care is often necessary for these women. Statistics reveal that as many as 37% of women who present to an emergency room, 21–66% seeking general medical care, and up to 20% seeking prenatal care have experienced IPV.5

Despite these statistics, less than 15% of these women report being asked about abuse in the health care setting.6 In one survey, when women survivors of IPV were asked to rank the professionals that were involved in their care, physicians were ranked lower than social service workers, clergy, the legal profession, and the police.10 However, health care providers, and especially obstetrician/gynecologists, are particularly well-suited to identify, assess, and initiate intervention for women involved in abusive relationships.11

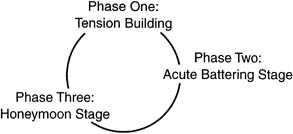

The identification of women who are victims of IPV must be incorporated into the routine care performed by obstetricians and gynecologists. The fact that the issue of IPV is not raised during routine examinations for all women seeking obstetric and/or gynecologic care is in part secondary to the lack of training and education among practitioners and to the societal misconceptions to which medical personnel are not immune. Practitioners often cite multiple reasons to rationalize their exclusion of this discussion as a routine part of patient care (Table 1). Also responsible are personal biases that all practitioners bring along to the practice of medicine. Foremost among these myths are the following: (1) IPV is rare.12 The traditional view of the family as a safe haven prevents acceptance of the fact that, for some, the family itself may pose a threat. Knowledge of the prevalence of IPV in the United States as well as in the practitioner's own community helps the practitioner realize that violence may be a part of the lives of patients and therefore must be addressed as a routine part of comprehensive health care; (2) IPV does not occur in normal relationships.10 This myth assumes that all abusers can be identified readily, and that violence is relegated to certain ethnic or socioeconomic groups. In fact, the health care provider may know and like the abuser, as has been demonstrated by celebrity cases highlighted in the media. IPV is not relegated just to women of specific ethnic or socioeconomic groups. In addition, most health care providers use a very narrow definition of what constitutes IPV. Physical violence is easier to see, but abuse also consists of sexual, emotional, economic, and verbal assaults. There is no real difference between these forms of abuse because all result in significant damage to the woman and her children; (3) women are responsible.12 It should not be difficult for practitioners to understand the barriers that face women involved in abusive relationships (Table 2). After all, medical personnel deal with issues far less immediately life-threatening to patients, such as diet, exercise, and smoking cessation, and have less success with these than they do with assisting a woman involved in a violent relationship. IPV, as with many other problems, may require frequent, repeated messages from physicians to convince battered women to stop their involvement with their abusive domestic partner; (4) IPV is a private matter.12 This is perhaps the most dangerous myth of all. Knowledge regarding the cycle of violence clearly demonstrates that abuse will escalate. As stated earlier, more than 50% of all female homicides are related to IPV.1, 7 Most physicians recommend marital therapy as the first step toward resolving issues of IPV, which may actually increase the lethality risk for women involved in these relationships. In addition, keeping IPV a private matter further serves to stigmatize the issue, thereby preventing interventions that could be life-saving. It is important for the practitioners to understand the cycle of violence so that they can appreciate the fact that violence escalates and that women may seek care only during certain periods of the cycle (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Reasons physicians do not screen for IPV

| Lack of training |

| Time constriction |

| Discomfort with role |

| Lack of understanding |

| Misperceptions |

| Powerless |

Table 2. Barriers faced by women

| Inability to recognize abusiveness |

| Cultural beliefs |

| Fear |

| Shame |

| Feeling that abuse is deserved |

| Blame |

| Denial |

| Hope |

| Financial worries |

CLUES TO THE PRESENCE OF VIOLENCE

Of all primary care physicians, obstetrician/gynecologists are perhaps the best suited to identify women who are victims of family violence because most women see their obstetrician/gynecologist for annual examinations, family planning, gynecologic symptoms, and obstetric care on a more regular basis. Clues to the presence of violence in the lives of women are both behavioral and physical. Behavioral clues that should increase the index of suspicion for violence include missed appointments, repetitive psychosomatic symptoms, depression (including suicide attempts), being accident prone, substance abuse, poor reproductive history, vague and inconsistent descriptions of injuries, delay in seeking attention for injuries, partner's demeanor and behavior in the medical setting, and the patient's direct report of abuse. The demeanor of the woman during the history and physical examination can include a flat or sad affect, embarrassment on the discovery of injuries, hesitance in discussing issues, apprehension about discussing her injuries, evasiveness, and even anger. All of these responses to a life of violence are acceptable, because there is no one set way in which abused women will respond when asked about injuries acquired as part of domestic abuse. Her response may be colored by past experiences with professionals, where she is within the cycle of violence, and the lethality of her particular circumstance.

The physical examination can further aid in the identification of women who have been abused. The injuries in women who have experienced IPV tend to occur in a pattern that is generally not visible when the woman is clothed (bathing suit appearance) or in the head and neck region. Injuries are usually multiple and out of phase, and the explanation given for their presence does not fit with either the injury itself or the age of the injury (Table 3). During the examination, the woman's partner may stand and watch the examination, answer all questions directed to the woman, and appear overly solicitous; he may even refuse to leave the examination room. This is of particular importance if the partner is the primary translator for a woman who does not speak English. The abuser may also test the limits of the medical visit, exhibiting hostile and surly behavior toward the staff. These clues should alert the physician to the possibility of IPV.

Table 3. Common injuries in IPV

| Bruises |

| Cuts |

| Black eyes |

| Concussions |

| Broken bones |

| Miscarriage |

| Joint damage |

| Loss of hearing/vision |

| Scars from bites, knife wounds, burns |

Specific gynecologic indications of IPV include sexually transmitted disease, pregnancies, chronic pelvic pain, sexual dysfunction, recurrent vaginal infections, and premenstrual syndrome. When the obstetrician/gynecologist is faced with these problems without any physiologic confirmation (especially if symptoms are repetitive), IPV must be considered.

CONFRONTING THE ISSUE

In addition to recognizing the problem, physicians must provide a secure environment in which the woman can feel comfortable talking, can validate her experience as a serious problem, and can record the occurrence and the effects of the violence. Asking about violence in a direct fashion communicates to the patient that the physician is willing to help and is aware of the patient's problem. Victimized women are more likely to disclose the circumstances of their victimization to other women and to personnel who offer protection and are sympathetic to the plight of battered women.13, 14 Therefore, the services of other personnel in the physician's office, clinic, or hospital must be integrated into the care of the abused woman. Educating staff members about the signs and symptoms of IPV may prove to be an invaluable step in the identification of women suffering spousal abuse. In addition to asking the question on a routine basis, having posters and pamphlets clearly visible in patient areas also communicates that this is a safe haven where the issues of IPV are understood. The bathroom in the medical office is one of the few places where the woman will be unaccompanied; strategically placing posters and cards with hotline numbers or the numbers of local agencies can be invaluable here. Not only can the woman receive the message that this is a place of support for her plight but also can she take steps toward leaving the abusive relationship in her own time frame.

After a disclosure about IPV to a physician, nurse, or social worker, the woman should be seen as quickly as possible by an advocate or social service representative who can provide her with information about her legal rights and, when needed, shelter.13

HOW TO ASK

When women are asked about violence directly and routinely, in a way that is not threatening, they will discuss their abuse, particularly if they believe that the health care provider really wants to know.15 The medical ethical principle of beneficence requires physicians to intervene in cases of IPV. When physicians do not diagnose abuse, the abuse will most likely continue and will often escalate. The interview approach should include directly and gently questioning all women about the presence of violence in their lives.16 Questions can be phrased as, "We know abuse by a woman's partner is a very common problem. Is that happening to you?" or "Because there is help available for women who are being abused, I now ask every woman about violence in her life" or "I do not know if this is a problem for you, but because so many women I see are dealing with abusive relationships, I have started asking all of my patients about it routinely”.17 The phraseology can be either ubiquitous (because violence is so common in many women's lives, I have begun to ask my patients about it routinely) or direct (are you in a relationship with someone who threatens or physically hurts you? Are you afraid of anyone at home? Did someone cause these injuries? Do you know where you could go or who could help you if you were being abused?).17 If the answer to any of these questions is "Yes", then follow-up questions are in order, such as: "Would you like to talk about what has happened to you?" "How do you feel about it?" and "What would you like to do about this?"17

Perhaps even more disturbing for physicians is a "No" answer when all clinical indicators suggest that the woman is a victim of IPV. Understanding the reasons women cannot leave is helpful to the practitioner in accepting this response (Table 4). The inability of women to leave abusive relationships must be compared with attempts to stop smoking and other less complex life changes. The practitioner should not expect that a single question about what is obviously long-standing violence in the woman's life is going to miraculously cure the situation. The difficulties encountered by women leaving these situations are often overwhelming. What the practitioner can do is provide the woman with guidance regarding a safety plan for when and if she does choose to leave.

Table 4. Reasons women stay in abusive relationships

| Psychosocial |

| Economic |

| Cultural |

| Financial |

| Lack of education |

| Children |

| No place to go |

| Religion |

| Low self-esteem |

The patient's confidentiality must be respected during all questions about abuse. Any queries regarding the home situation must be asked with the patient alone, away from the abuser. In addition, any reporting (with the exception of child abuse reports) must be performed with the patient's expressed consent unless the physician is required by law to report a particular event.18 In these instances, the patient should be informed of what is required of health care providers when they become aware of certain circumstances and what the report will include.

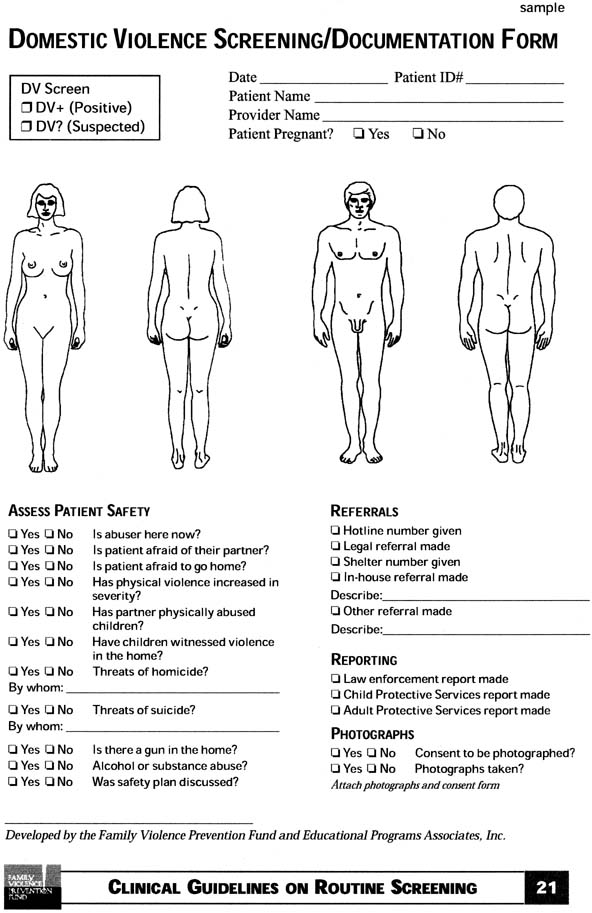

The opportunity to evaluate for the presence of injuries is more likely to occur during an obstetric or gynecologic physical examination, because of the nature of this examination, than it is during other primary care physician visits (e.g. upper respiratory infection, earache, headache, and so forth). Therefore, it is the obligation of the physician to recognize injuries that may be secondary to abuse. Typically, these injuries appear on portions of the patient's body that are usually clothed; therefore, they are hidden from friends, family, and neighbors. Bruises are usually of varying ages, and other injuries are in various stages of healing. The examining physician must question the presence of these injuries but must also ensure that acute injuries receive specific trauma care, if necessary. Documentation of all injuries must be part of the confidential medical record.19 Both the physical injuries and the emotional injuries must be addressed (Fig. 2). Often, outpatient therapy is sufficient. However, if injuries are severe or the situation is deemed to be lethal, then inpatient therapy is justified. The safety of the woman must be the first consideration under these circumstances.

Immediate care by the obstetrician/gynecologist should also focus on emotional support of the patient, including assurance that no one deserves to be battered and that the woman is not alone. Information regarding options and community resources should be given to the patient when IPV is discovered. The long-term goals of these interactions are to validate the woman's experience and to explore and advocate safe options while respecting her right to make her own decision about the next step. Finally, a follow-up plan should be devised when the obstetrician/gynecologist identifies or suspects IPV. This should include firm plans for a future visit as well as follow-up communication with the woman that is documented in the patient record. The follow-up plan serves to maintain open lines of communication for the patient while assuring that she and her children remain safe.

DEVELOPING A SAFETY PLAN

The assessment of lethality is the most important consideration when a women is identified as living with IPV. It is well known that the cycle of violence escalates over time and that the risk of life-threatening injury and homicide increases. Therefore, assessing the safety of the woman and her children is of primary importance. Queries regarding the presence of firearms, a previous history of threats to harm with firearms, or previous injuries with potentially lethal weapons should alert the physician to the lethal risk of this situation. Questions regarding safety must be posed to the woman at the time that IPV is identified. Models for assessing lethality in pregnancy (Abuse Assessment Screen) and in other clinical circumstances (SAFE questions) are available to practitioners.20, 21 These screening tools have been validated in clinical settings. They add very little time to the clinical interview and demonstrate the practitioner's desire to know about abuse and the safety of the woman. After she is assessed for lethality, the woman must be assisted in developing a plan of action to secure her safety and that of her children. The safety plan must include transportation, a place to go, necessary items for survival, and important documents (Table 5).

Table 5. Items women need when they want to leave a relationship

| Documents | Other |

| Driver's license | Emergency money |

| Birth certificate | Medications |

| Rental agreements | Keys |

| Bankbooks | Small toys |

| Insurance papers | Change of clothes |

| Titles/deeds | |

| Social security card | |

| Address book | |

| Work permits | |

| Passport/green cards | |

| Civil action papers | |

| School/health records |

PREGNANCY

IPV during pregnancy is not rare. It is estimated that up to 20% of pregnant women are victims of IPV and as many as 25–45% of battered women are battered during their pregnancies.2, 22 The more severe the abuse is before pregnancy, the more likely it is that abuse will continue and/or escalate during pregnancy.3 Indeed, 29% of battered women report an increase in abuse during pregnancy.6 One third of these women seek medical attention related to their injuries during pregnancy.6 The National Family Violence Survey, which evaluated more than 6000 women, reported that there were 154 acts of violence per 1000 women during the first 4 months of pregnancy and 170 acts per 1000 women during months 5 through 9.7 These data also suggest that a pregnant woman's risk of abusive violence is more than 60% higher than that for a nonpregnant woman.12 Fifty-five percent of women abused during the last year prior to pregnancy experienced abuse during pregnancy.10 Despite this information, our knowledge of abuse during pregnancy is limited. There are a lack of data on frequency, timing, and severity of injuries during pregnancy as well as a lack of stratified data on ethnic and other demographic variables.13

It is well known, however, that abuse during pregnancy poses significant risks for both mother and fetus. The adverse effects of abuse during pregnancy result from either direct or indirect causes. Direct causes of adverse perinatal effects include abruptio placentae; fetal fractures; rupture of the maternal uterus, liver, or spleen; maternal pelvic fractures; and antepartum hemorrhage (Fig. 3).13 Indirect effects include maternal stress, isolation of the mother and inadequate health care, behavioral risks such as substance use, and inadequate maternal nutrition (either secondary to emotional factors or as part of the abuse cycle). For the practicing obstetrician/gynecologist, pregnancy presents a unique opportunity to form a partnership with a woman for the identification and assessment of IPV. Pregnancy may motivate women to seek help from abusive relationships. It may also be the only time that a woman seeks medical attention. The fetal consequences of the abuse may be the factor that motivates the woman to take steps to remove herself from the abusive situation.

Data suggest that IPV determines the trimester during which women will seek care during pregnancy.3 Abused women are three times more likely to seek care in the third trimester. In fact, the abuser may force the woman not to seek earlier care by denying transportation, nutrition, and access to medications (antibiotics, vitamins). Because injuries around the head and neck are publicly visible, evidence of the abuse may contribute to missed appointments. Women who begin prenatal care late may have only one opportunity to obtain information on abuse and be given options for maternal and fetal safety.

MEDICOLEGAL CONSIDERATIONS

All physicians are required to keep comprehensive medical records for all patients, and these records must document the woman's report of abuse.23 The records should contain the patient's statement about the abuse, the medical findings, and the physician's opinion regarding the physical findings.19 Photographs can be used; however, they must be handled properly. In most circumstances they should be handled by law enforcement specialists. They must also be kept in a sealed envelope so that they can be admissible for courtroom use at a later date, if necessary. Finally, under certain circumstances, a report must be filed with the police.24 Any cases in which children are involved in the abuse must be reported by medical personnel. Other cases that must be reported include attempted murder, assault with a deadly weapon, and other potentially lethal incidents. US laws regarding the reporting of these events vary from state to state and within municipalities. It is the physician's responsibility to be aware of the particular reporting requirements in his or her state of practice and/or community.

COMMUNITY RESPONSE

An integral part of providing care to women is establishing a relationship between the obstetrician/gynecologist and hospital or office staff and the community. Part of the development of safety plans for women who are victims of IPV is to identify what resources are available within the health care provider's community. The principles of this community relationship include ensuring the safety of the woman and her children, respecting the woman's integrity and authority, holding the perpetrator responsible for abuse, providing advocacy for women and children, and improving the response of the health care system. Resources that should be available in every community include emergency housing, psychological counseling, legal counsel, and other support. Unfortunately, there is often no safe haven available for women and their children when they leave abusive homes. In fact, in the United States there are more animal shelters available than there are shelters for women and their children.

In the event that a woman's community lacks any resources, a US national hotline number, 1-800-333-SAFE, is available to refer clients to the nearest available shelter. By developing a relationship with the physician, other health care providers, and staff, identification and intervention can be assured. In addition to resources for women, services for abusers are also available that focus on goals to end violence. Within these programs, the abuser learns to accept responsibility for the violence, to develop skills to change behavior, to end the violence, and to develop nonviolent attitudes and behaviors.

SUMMARY

To adequately address the issue of IPV in their patients, all obstetrician/gynecologists must routinely ask about abuse while assuring patient safety and confidentiality and documenting all findings. What the obstetrician/gynecologist should recognize is that this assessment is intervention, as reflected by the fact that only 8% of women will self-report abuse but 29% will report it when asked by a health care provider.25, 26, 27 With knowledge of community resources, appropriate referrals and follow-up can be assured. What health care providers cannot do is stop the violence, make choices for patients, and fix all of the links of these complex issues.

IPV is part of a continuum of violence involving not only partner abuse but child abuse, elder abuse, and sexual assault. A related matter is that violence is costly, not just to the individuals but to society. Emergency room statistics from the US reveal that up to 37% of women with any complaint are seen secondary to IPV, and at least 1000 women each year are killed by their partners. Homicide is the leading cause of death of women in the work place.28 The cost to the public of this hospital care is billions of dollars annually. The obstetrician/gynecologist must assume the role of the agent of change through the identification of abused women, awareness of the prevalence of abuse, the assessment of women who are victims of IPV, and linkages with community resources.29 Physicians must validate the unacceptability of violence and the right to safety for all women and their children. Obstetricians/gynecologists are in a unique position to offer support in a nonjudgmental fashion while providing viable alternatives. Women must be enabled to live their lives free from violence, both inside and outside the home.30

REFERENCES

Koop CE: Former Surgeon General of the United States. |

|

Strauss MA, Gelles AJ, Steinmetz SK (eds): The marriage license as a hitting license. Behind Closed Doors. Violence in the American Family. pp 31-50, New York, Anchor, 1989 |

|

Salber PR: New requirements aimed at improving the care of battered women. San Fran Med April:20, 1992 |

|

Plichta SB: Violence and abuse: Implications for women's health. Women's Health: The Commonwealth Fund Survey. pp 237-270, Baltimore, MD, Johns Hopkins University, 1996 |

|

Rodriguez MA, Bauer HM, McLoughlin E et al: Screening and intervention for intimate partner abuse: practices and attitudes of primary care physicians. JAMA 282:468, 1999 |

|

Abbott J, Johnson R, Kozial-McCain I et al: IPV against women, incidence and prevalence in an emergency department population. JAMA 273:1763, 1995 |

|

National Institute of Justice and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: 1998 |

|

Paulozzi LJ, Salzman LE, Thompson MP, Holmgreen PH. Surveillance for homicide among intimate partners-United States 1981-1998. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ 2001;50(3):1-15. |

|

Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full report of the prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women: findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington DC: US Dept. of Justice, National Institute of Justice;2000. NCJ 183781. |

|

Jecker NS: Privacy beliefs and the violent family: Extending the ethical argument for physician intervention. JAMA 269:776, 1993 |

|

Plichta SB, Falik M. Prevalence of violence and its implications for women's health. Women's Health Issues 2001;11:244-58. |

|

Sugg NK, Inui T: Primary care physicians' response to IPV: Opening Pandora 's Box. JAMA 267:3157, 1992 |

|

Newberger EH, Barkan SE, Lieberman ES et al: Abuse of pregnant women and adverse birth outcome. JAMA 267:2370, 1992 |

|

Rodriguez MA, Sheldon WR, Bauer HM, Perez-Stable EJ. The factors associated with disclosure of intimate partner abuse to clinicians. J Fam Pract 2001;50:338-44 |

|

Rath G, Jarratt L: Battered wife syndrome: Overview and presentation in the office setting. South Dakota J Med 43:19, 1990 |

|

Gelles R: Violence and pregnancy: Are pregnant women at greater risk of abuse? J Marriage Fam 50:841, 1988 |

|

Chez RA, Jones AF: The battered woman. Am J Obstet Gynecol 173:677, 1995 |

|

Family Violence Prevention Fund. State-by-state legislative report card on health care laws and domestic violence. San Francisco (CA): FVPF;2001. |

|

Rudman WJ. Coding and documentation of domestic violence. San Francisco (CA): Family Violence Prevention Fund; 2000. |

|

Parker B, McFarlane J: Identifying and helping battered pregnant women. Matern Child Nurs J 16:161, 1991 |

|

Asher MLC: Asking about IPV. SAFE questions JAMA 269:2367, 1993 |

|

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Domestic Violence. ACOG Technical Bulletin 209. Washington DC; ACOG 1995 |

|

Family Violence Prevention Fund. Summary of new federal medical privacy protections for victims of domestic violence. San Francisco (CA): FVPV; 2003 |

|

Rodriguez MA, Craig AM, Moonoey DR, Bauer HM. Patient attitudes about mandatory reporting of domestic violence. Implications for health care professionals. West J Med 1998:169; 337-41. |

|

McFarlane J, Christoffel K, Bateman L et al: Assessing for abuse. Self-report versus nurse practitioner interview Public Health Nurs 8:245, 1992 |

|

Strauss MA, Gelles R: Societal changes and change in family violence from 1975–1985 as reviewed by two national surveys. Family 48:465, 1986 |

|

Horan DL, Chapin J, Klein L, Schmidt LA, Schulkin J. Domestic violence screening practices of obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92:785-9. |

|

McFarlane J: Abuse during pregnancy: The horror and the hope. Assoc Womens Health Obstet Neonat Nurs Clin Issues 4:300, 1993 |

|

Jones RF, Horan DL. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: a decade of responding to violence against women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1997;58:43-50. |

|

Novella AC: A medical response to IPV. JAMA 267:3132, 1992 |